Rap music in Turkey is no longer a genre of music. It has ceased to be a field of cultural expression; it has become the rhythmic interpreter of class oppression, political despair and anxiety about the future. Therefore, it is a conscious diversion to discuss rap only on aesthetic, moral or criminal grounds. Rap is the echo of a regime's failed relationship with the youth in Turkey today.

Rap music in Turkey is no longer a genre of music. It has ceased to be a field of cultural expression; it has become the rhythmic interpreter of class oppression, political despair and anxiety about the future. Therefore, it is a conscious diversion to discuss rap only on aesthetic, moral or criminal grounds. Rap is the echo of a regime's failed relationship with the youth in Turkey today.

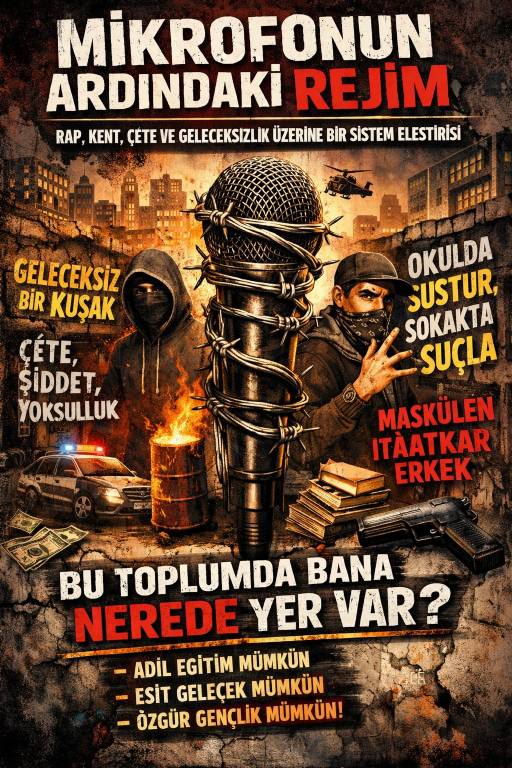

The government sees the youth not as a subject but as a mass to be managed. This perspective suppresses the political demands of the youth, postpones their economic expectations and directs their cultural energy to harmless areas. At this point, rap functions as a “controlled ejaculation space”: You can shout but you cannot demand. You can rage but you cannot organize. There is rebellion but no target.

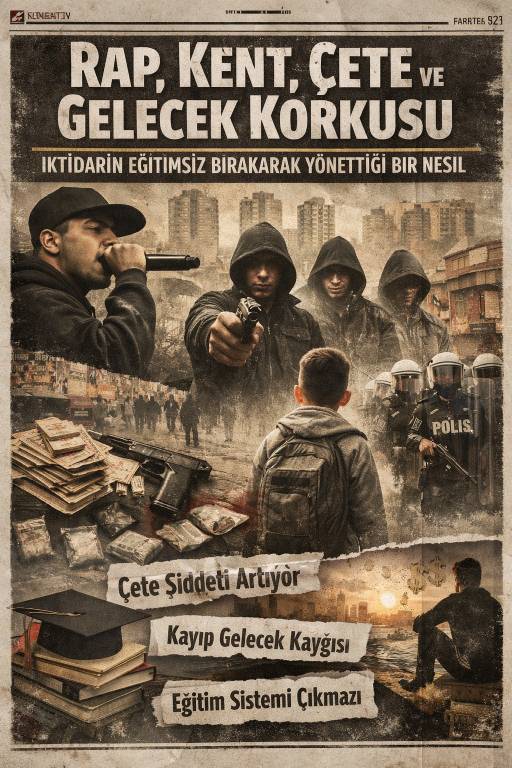

No Future The Real Trauma of Youth

Today, it is not ideology, but a lack of future that is at the root of the youth's turn towards violence, gangs and rigid identities. This generation is learning to survive, not to dream. A university degree is no longer a means of moving up in class, but a deferred form of unemployment. For young people, merit is a theoretical concept; torpil is a daily reality.

When the state fails to offer youth a long-term narrative of the future, youth turn to short-term means of status. The images of power, money and violence in rap fill this void. The individual without a future exaggerates the present. He hardens. He takes risks. He gets closer to the gang. Because there is no tomorrow.

Education System: A Factory That Does Not Produce Hope

The education system in Turkey no longer produces knowledge; it produces obedience and competition. Schools teach children to adapt, not to think. The critical mind is systematically pruned. The exam-centered structure turns children into rivals, teachers into auditors and education into a traumatic elimination process.

In this system, children learn that:

Be quiet. Adapt. Don't look up.

Education ceases to be a space that builds public consciousness; it turns into a politically neutralized space. Then the same state complains about a youth that is not politically conscious but recognizes violence. This is not a contradiction; it is a result.

Identity Caught Between Rap and School

The child who is silenced in the classroom shouts on the street. The youth devalued at school seeks respect in the neighborhood. The child whom the teacher does not recognize cares about the attention of the gang leader. Rap is the language of this transitional space. The street produces the meaning that the school cannot give with its own codes.

At this point, gangs are not a deviation; they are an alternative form of socialization that emerges in areas abandoned by the state. Where there is no state, other authorities emerge. This is a sociological rule.

Masculinity The Oldest and Most Functional Tool of Power

The masculinity reproduced in rap is not an individual aesthetic preference but a historical technique of power. Tough masculinity is submissive masculinity. The man who directs his power towards others does not question the source of power. The man who shakes his fist in the neighborhood does not think about why it always comes down.

Foucault’s body politics works here in its naked form: The state no longer disciplines with the baton, but with culture. This aesthetic, which forces the male body to constantly prove itself, turns young people into both perpetrators of violence and voluntary carriers of the system.

It is no coincidence that even female rappers reproduce the same codes of harshness, honor and violence. This shows that patriarchy is a cultural continuity independent of power. Powers change, but the language of power remains.

Gangs, Crime and Selective Blindness

In Turkey, gangs are deliberately confined to a narrow criminal sphere. However, gangs are not only criminal organizations but also social gap fillers. Wherever the state withdraws, there are gangs. The family dissolves, school becomes inadequate, social policy retreats; the “big brother” figure fills the void.

The government deals with the swearing, the image, the aesthetics in rap; but it does not see the poverty and inequality that this aesthetics feeds on. Because gangs organize young people against each other, not against the state. For this reason, it is tolerated for a long time.

Law works downwards here. The child is judged, but the networks that put him there remain invisible. This is not justice, but a pushing down of responsibility.

Neoliberal Order and Commodification of Culture

When the government abandoned the claim of a social state, it also handed over the youth to the market. Culture is no longer a public right, but a consumable product. Rap is one of the most profitable commodities of this market. The anger of the youth turns into watching, sharing and advertising.

Adorno’s critique of the culture industry is exactly valid today: Dissent is aestheticized, packaged and rendered harmless. The system is not disturbed by this order, because as long as anger is not politicized, it is safe.

The Political Suspension of a Generation

Today the youth is neither in power nor in opposition. It is in a vacuum. This void is filled with gangs, violence and hard identities. Because politics cannot offer the youth a promise of a future.

This youth is not apolitical; it is politically excluded.

Where to Exit?

To change this picture, the state, civil society and the culture industry need a radical change of mindset, not a makeover. The issue is not about banning or sanctifying rap; it is about recognizing why youth are forced into this language.

There should be space for young people to use rap as a form of expression, but this space should not be a sterile showcase of freedom where images of violence and crime are not questioned. When freedom of expression is decontextualized, it does not liberate; it normalizes. For this reason, the codes of power, weapons and status circulating in rap should be made debatable with their social consequences, without romanticizing them.

In schools, cultural centers and neighborhood workshops, young people should learn not only how to make music, but also its history, class roots, political background and effects. Rap is not a rhythm; it is a carrier of memory and ideology. As long as the youth does not recognize the language they use, they are ruled by that language.

Discussing rap only from the perspective of freedom of expression renders the responsibility of the government invisible. However, rap has real-life counterparts: peer bullying, gangs, early criminalization and hardened identities. For this reason, rap should be at the center of education, youth and social justice policies, not cultural policies.

This issue cannot be solved by security policy. It cannot be solved by police, banning or censorship, but by the construction of public space. The state should not just tell young people to “stay away”; it should show them where to go.

Rap is not just a music genre in Turkey today. It is a critical cultural space that redefines social inequality, the search for belonging, peer bullying, gangs and the power of the media. To confine this space to the axis of crime and punishment is to deny both the potential of music and the reality of young people.

And most importantly: To see rap as mere entertainment consumed on stage is to ignore the search for identity and a future by millions of young people. What lies behind the microphone is a question deeper than violence:

“Where is there room for me in this society?”

While the system continues this silent attack, we still applaud it as “original art”. But what is being applauded is the slow loss of a generation.

There is no heavier defeat for a society.