The real crisis of the opposition in Turkey is no longer the pressure of the government; it is the opposition's own understanding of politics. The distance between what they say and what they do has widened so much that this gap has become more visible, more burning and more instructive than all the authoritarian moves of the government. CHP deputies' demand for an increase in the pensions of pensioners started in the General Assembly of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and has been going on for days. “seizure.” is the most recent, clearest example of this crisis.

The real crisis of the opposition in Turkey is no longer the pressure of the government; it is the opposition's own understanding of politics. The distance between what they say and what they do has widened so much that this gap has become more visible, more burning and more instructive than all the authoritarian moves of the government. CHP deputies' demand for an increase in the pensions of pensioners started in the General Assembly of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and has been going on for days. “seizure.” is the most recent, clearest example of this crisis.

It is called a vigil. But it is unclear what it expects, whom it aims to force, what social power it relies on. Is this a political action or a well-intentioned show of conscience? If politics, where is the result? If it is conscience, what historical evidence do we have that the government acts with conscience?

This action, held under the warm roof of the Parliament, is nothing more than a symbolic gesture. Every “objection” made in heated halls, in a place where cameras are familiar, is not a threat to the government; it is a manageable routine. However, the issue of pensions is not a technical budget issue, but a class fracture line. This is where real politics begins: In life, on the street, in the square, with a pressure that disrupts the daily order.

Without coordination with trade unions, pensioners' organizations, professional associations, without moving tents to city squares, without weaving a simultaneous social objection all over the country, every action can only distract the opposition's own base, not the government. Because the government understands pressure, not words. If there is no pressure, there is no politics.

The real problem here is not the weakness of a singular action, but the fact that this weakness has turned into a choice. The CHP's political style in recent years has been shaped by the reflex of confining the struggle to controlled areas. Speaking at the Parliament, making press statements, holding symbolic vigils... These are all “harmless” actions. Actions that do not involve risk, that are predictable, that do not shake the order.

However, politics begins precisely when risk is taken. The street is risky, the square is risky, organized anger is risky. And it seems that the CHP is consciously avoiding this risk.

What is more striking is that even the opposition parties in Parliament cannot come together around this action. Why should the government take seriously an opposition that cannot even agree on the most basic issue of social justice? What kind of political mind is it to expect an opposition that cannot even fill its own desks to raise an eyebrow in the Palace?

At this point, the question cannot be postponed any longer:

Do they really believe that a sit-in, which even the opposition parties did not support and failed to stand side by side, will disturb the government?

The government is not disturbed by such actions; on the contrary, it is relieved. Because a fragmented, symbolic and controlled opposition is not a threat to the government; it is a comfort zone. If there is no street, there is no pressure. Without pressure, politics slowly turns into a ritual.

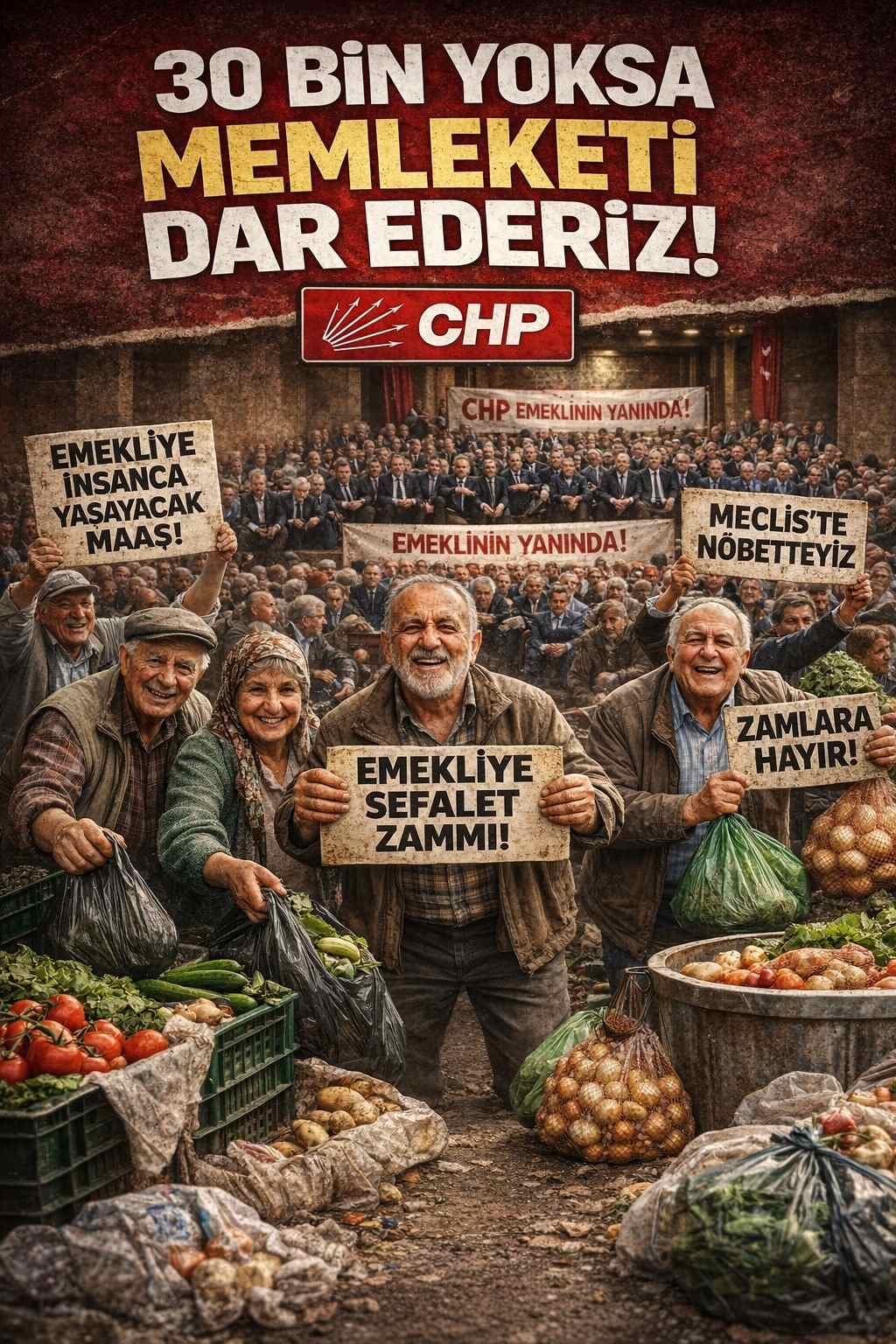

We need to refresh our memory here. Just two years ago “if the minimum wage is below 30,000 liras, we will make the country narrow” "I'm not going to do this, I'm not going to do that. Big sentences, high tone, harsh challenges... Today we have reached the point where “don't make the country narrow” is reduced to sitting in the parliament. There is no picket line, no square, no social mobilization. There are words but no action.

This is not just an inconsistency, but a sign of a political transformation. The CHP is increasingly “candidates to govern but not to fight” It turns into a party. It assumes a role that calms society instead of mobilizing it, that absorbs anger instead of organizing it. This inevitably raises the question: Does the CHP really want to challenge the government, or is it looking for a reasonable place in the establishment?

If the problems of the pensioners, the minimum wage earners, the unemployed and the precarious are to be passed over with symbolic gestures in parliament, the difference between the presence and absence of the opposition will become increasingly blurred. Politics loses its meaning the moment it does not touch the lives of the masses it represents.

Vigils in Parliament are no substitute for broken promises on the streets. Demonstrations of conscience in heated halls do not warm cold homes. And “we'll make the country a real mess” The fact that a political mind that reduces the country's hardship to sitting in the parliament is the bankruptcy not only of the government but also of the opposition.

As a result, we have the following picture:

An opposition that cannot unite within itself, that cannot risk the streets, that does not prefer pressure... Such an opposition is not an obstacle to the government; it is its insurance.

The question now is:

Is the CHP in opposition or does it pretend to be in opposition?

The answer to this question will not only determine the future of the CHP, but also the future of Turkish politics.

However, one more dimension needs to be added to complete this picture: A significant part of the CHP's political energy today is not focused on building a populist politics, but on a Silivri-centered narrative of political destiny and Ekrem İmamoğlu's future. Silivri, beyond being a justice issue, is increasingly turning into a political comfort zone for the CHP. The struggle is being squeezed into a narrative of victimization based on possible judicial processes, not around social demands.

This creates a contradiction in itself. Because when the political horizon of a party is so tied to the future of a single name, populist politics inevitably becomes secondary. The pension of the pensioner, the security of the worker, the table of the poor; all of these are the concerns of a “future calculation”becomes a background scenery. Politics ceases to be a collective claim for social transformation; it is reduced to a scenario of personal salvation.

Silivri is of course important. Of course, lawlessness requires objection. However, if the main energy of an opposition party is directed not towards transforming the daily lives of large segments of society, but towards consolidating the political future of a leader, there is no populist politics.

And at this point, the recent past should not be forgotten.

Despite all its shortcomings, the CHP under Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu was able to pursue an integrative, reconciliatory and bloc-building line that did not confine politics to gestures within the Parliament. The Table of Six was not a showcase of leaders, but an attempt to bring different political and social segments together. This approach represented an opposition approach that expanded politics, not narrowed it.

More importantly, this politics was taking to the field. There was an opposition practice that stood on the doorstep of TÜİK and held it to account with figures, that went in front of SADAT and challenged the shadowy structures, that directly contacted areas of the state that were considered untouchable. These actions were not controlled, they were not comfortable; they were risk-taking and that is precisely why they disturbed the government.

This practice had concrete achievements. Steps such as two bonuses for pensioners, the EYT regulation, improvements in salary coefficients, bringing the issue of the staffing of subcontracted workers to the center of the political agenda, and the cancellation of KYK debts were the product of persistent political pressure, not just rhetoric. These were not promises, but achievements.

Therefore, the issue is not nostalgia. The issue is which style of politics produces results. A politics that integrates, takes the field, holds to account and creates social pressure; or an opposition that waits, postpones and stalls in Parliament?

This is precisely the real choice facing the CHP today.

Therefore, it is clear from the very beginning that this sit-in in the parliament will not bring a single concrete gain to the pensioners. This action does not force the government, nor will it change any of its decisions. Despite this, CHP, “we took action” and turns it into a propaganda tool. But this is a practice of action that does not produce results.

What is even more serious is this: All of the MPs who participated in this sit-in in the Parliament know that it will not bring any gains to pensioners. Despite this, posts are shared without shame or embarrassment as if a historical struggle has been waged; a symbolic gesture is presented as a real political move. This is the clearest indication that politics is not done on behalf of the people, but for the showcase.