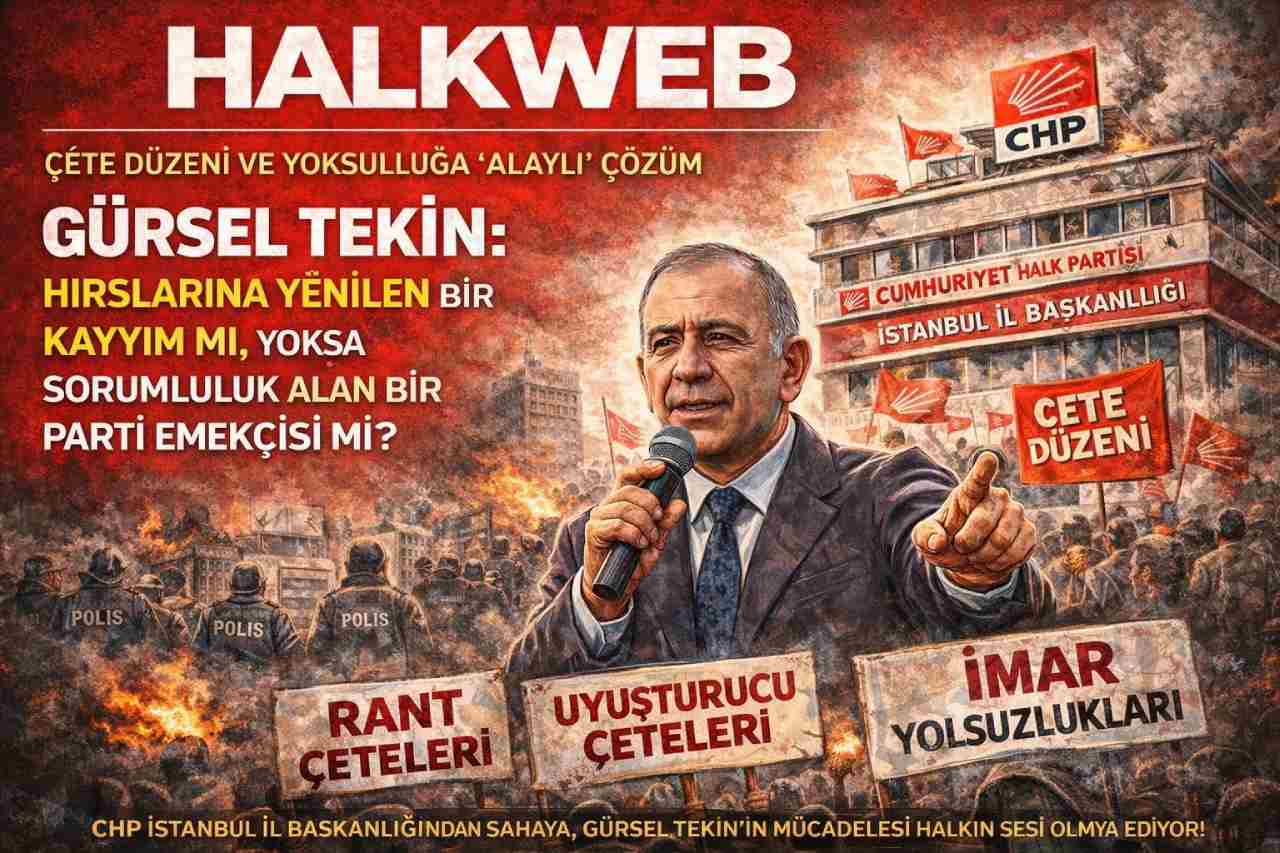

There are some debates in Turkish politics that ostensibly center on a person, but in reality target a regime, a party model and a political understanding. The storm around Gürsel Tekin is exactly like this. The debate is not limited to what Gürsel Tekin did or did not do. The debate is about the question of what kind of politics the CHP and the opposition more broadly will do.

There are some debates in Turkish politics that ostensibly center on a person, but in reality target a regime, a party model and a political understanding. The storm around Gürsel Tekin is exactly like this. The debate is not limited to what Gürsel Tekin did or did not do. The debate is about the question of what kind of politics the CHP and the opposition more broadly will do.

Therefore, defending Gürsel Tekin is not a matter of personal loyalty. This defense is a clear position against the technocratic sterilization of politics, central tutelage and the pushing of the organization out of politics. The attacks against Gürsel Tekin today are in fact “too much talking”, “too much on the ground”, “too much disturbing” is an attempt to liquidate politics. The target here is not an individual actor, but an organized, field-based and uncontrollable form of politics.

This debate within the CHP is part of a wider context. The opposition in Turkey has long shown a tendency to de-risk political struggle, minimize conflict and reduce politics to a technocratic administration. This tendency transforms the organization from being the subject of politics into an apparatus that implements the decisions of the center. The Gürsel Tekin debate emerged precisely at this breaking point.

The Beginning of the Legal Crisis

When the governance crisis in the CHP Istanbul Provincial Organization moved from a political debate to a legal stage, the nature of the process changed. Lawsuits filed by party delegates and members brought the issue before the judicial authorities. The court in charge of disputes concerning the provincial and district organizations of political parties is not the Constitutional Court, but the Civil Courts of First Instance with general jurisdiction. This is a technical but decisive distinction.

The main issue before the court is this: Has the current provincial administration ceased to function legally and has an extraordinary congress become mandatory? In seeking an answer to this question, the judiciary did not seek to seize the party or directly appoint an administration. On the contrary, it has put in place an intermediate mechanism that would cause the least possible damage to politics.

Activation of the Call Committee Mechanism

The court's decision does not suspend the administration of the party or impose an external will. The decision is merely the operation of the mechanism of the call committee tasked with convening the extraordinary congress. This mechanism exists in political party law to prevent organizational deadlocks from turning into depoliticization.

The call committee is not a locus of power. It is temporary, has limited authority and its sole purpose is to ensure the reproduction of the elected will. In this respect, the call committee is the opposite of a trustee; it is a tool for the continuation of politics, not its suspension.

In the case of political parties, the Courts take it as a basis that, whenever possible, the solution should be generated from within the party itself. For this reason, it was preferred that the call committee consist of names who know the party culture, have organizational memory and have political legitimacy. This preference is a political as well as a legal obligation.

The Birth Moment of the Trustee Discourse

It is precisely at this point that the mechanism of the call committee began to be deliberately distorted. Gürsel Tekin's acceptance of this task, “trustee” and presented as a legal obligation and a political usurpation. However, the real picture is quite the opposite.

If Gürsel Tekin had not accepted this assignment, the process would have been carried out by lawyers assigned by the bar association, and the CHP would have been under de facto legal tutelage. So there were two options: Either an actor from within politics who knew the organization would take responsibility; or the party would be depoliticized by the law.

What Gürsel Tekin has done is not to seize the party, but to prevent the law from turning into an instrument to liquidate politics. Therefore, what is “trustee” here is not what is done, but what is prevented from being done.

What Would Have Happened If Gürsel Tekin and His Friends Had Not Accepted the Call Committee Assignment?

If Gürsel Tekin and those who took responsibility together had not accepted the task of the call committee, the CHP Istanbul Provincial Organization would have lost the opportunity to produce a political solution; the process would have been left entirely to the initiative of the legal bureaucracy. Lawyers appointed by the bar association would have stepped in to convene the extraordinary congress, and the party would have de facto turned into a legal object that had lost its organizational will. In this case, the issue would not only be the governance of a provincial organization; the CHP would have accepted to solve its internal crisis through the judiciary, not politics. Therefore, not taking on the task of the call committee would not mean “neutrality” or “holding back”; it would mean consenting to the liquidation of politics. What Gürsel Tekin and his friends did was not to avoid the risk, but to consciously assume the most costly political position in order to prevent the party from falling under legal tutelage.

The Duty of the Call Committee: A Display of Ambition or the Responsibility of Party Workers?

With the acceptance of the task of the call committee, the direction of the discussion was consciously personalized. A legal obligation and an organizational responsibility have been compressed into the narrow patterns of political polemic and presented under the title of “personal ambition”. However, such accusations often serve more to discredit the actor taking responsibility than to produce political analysis.

Ambition in politics is not about taking risks; it is about avoiding them. Ambition is not paying the price, retreating, remaining silent and managing to stay in the center under all circumstances. Those who do not take responsibility in times of crisis, who put the burden on others and are content to watch the outcome are often presented as “smart” and “measured”. Yet those who carry the burden of politics are often labeled as “ambitious”.

The task of a call committee is not a comfort zone. On the contrary, it carries the risk of legal uncertainty, intense criminalization, becoming an internal party target and personal political attrition. Taking on such a position is not a career gain; it is a conscious choice to pay a price.

At this point, the concept of “party laborer” becomes decisive. Being a party worker means not disappearing in times of crisis, not passing the burden to someone else and taking the initiative to prevent the disintegration of the institutional structure. Gürsel Tekin's acceptance of the call committee task is precisely the product of this laborer understanding of politics.

What is on display here is not ambition but an ethic of political responsibility. Preventing the legal vacuum within the party from turning into depoliticization means risking to pay a collective price, not personal gain. This attitude makes sense on the ethical ground of organized politics, not careerist politics.

Therefore, the question is not “Why did Gürsel Tekin get this assignment?”. The real question is this: Who did not want to take this responsibility? Who preferred to remain silent, to retreat and to burden the process on the backs of others? Because ambition in politics is not in taking responsibility; it is in avoiding responsibility.

A Line from the Organization to the Center: Gürsel Tekin's Political Origins

Gürsel Tekin's political background does not resemble the career of a centrally appointed showcase figure. His politics has been shaped starting from the lowest levels of the party organization and has been kneaded in the field, in the neighborhood and at the district level. This background is the main factor that determines his political style.

Organization-based politics is fed by concrete contacts, face-to-face relations and daily problems, not abstract strategy documents. In Gürsel Tekin's political practice, the organization is not an “election machine” but the carrier of social demands. For this reason, the bond he establishes with the organization is not representative; it is permanent.

This line also explains why he is always at the center of the debate. Actors with strong ties to the organization, who know the field and do not fit neatly into central control mechanisms are always seen as “difficult to control”. Gürsel Tekin's political adventure has progressed precisely under the shadow of this fear of lack of control.

Istanbul Provincial Presidency: The Experience of Field-Based Opposition

One of the most critical thresholds in Gürsel Tekin's political career is his term as CHP Istanbul Provincial Chairmanship. Being provincial chairman in a city like Istanbul, where rent pressure is high and local power networks are extremely strong, is not a low-profile task. This was a period in which the CHP re-established contact with street politics after a long time, and the organization moved from being a passive signboard to actually taking to the field.

In this process, the party came into direct contact and clashed not only with the government, but also with the established relations, zoning and rent networks within the opposition. These conflicts, far from strengthening Gürsel Tekin's position within the party, made him a controversial and disturbing figure. It is precisely for this reason, however, that this period has been recorded as an important experience of field-based opposition.

Parliamentary Term: Stepping Out of Comfortable Opposition

Gürsel Tekin's term as an MP does not follow a line that wanders in the safe and repetitive areas of parliamentary politics. Drug trafficking, street gangs, missing children, deep and persistent poverty, the rent system and zoning policies in metropolitan cities were among the topics he insistently raised in his parliamentary work.

These spaces are politically risky. Because addressing these problems requires confrontation not only with the government but also with local power centers, invisible networks and the silence within the opposition. For this reason, Gürsel Tekin's practice as an MP has not made him a safe opposition figure. On the contrary, it has placed him in the position of an actor who disturbs, asks questions and cannot be easily dismissed.

Social Courage, Not Social Policy

Topics such as drugs, gangs, disappearance of children or urban poverty are not just a matter of social policy; they are a matter of political courage. Gürsel Tekin's insistence on these issues has not made him popular, but it has brought politics into contact with real problems. Social courage is not doing politics to get applause; it is doing politics to make the problem visible.

First Consensus, Then Trap

At the point of the call committee process, contacts were established with the party headquarters and an agreement was reached on how the process would proceed. However, this consensus was consciously turned inside out at the last moment. A previously discussed process was presented as an “extraordinary threat”. This is a preference for perception management, not political reality.

Digital Lynching, Perception Management and the “5000 Cops” Narrative

One of the most visible tools of the criminalization process is digital lynching. The claim that “he came with 5000 police officers” is technically and logically inconsistent. The total number of riot police personnel on duty throughout Istanbul is already around 5000. This number refers to a security capacity that is spread across the entire city, not to thousands of policemen piled up in a single party building. If all the riot police in Istanbul were deployed in a single location, the question of how public order would be maintained in the rest of the city would remain unanswered. For this reason, the “5000 police” narrative is not information; it is a caricature of perception aimed at generating fear.

What Does Silence Say? Where were the tens of thousands?

It is not a coincidence that tens of thousands of CHP members were absent the day Gürsel Tekin arrived at the provincial building. If there really was an extraordinary crisis, the Istanbul provincial building would have been filled with tens of thousands. The absent crowds show that the story being told does not resonate on the ground.

The systematically circulated rumors about Gürsel Tekin “He has 300 apartments”, “he has petrol stations” His allegations are not political polemics; they are a clear set of slander that has no legal equivalent. In Turkey, real estate ownership is subject to the land registry and commercial enterprises are subject to the trade registry; these records are public and auditable. Despite this, those making these allegations have not been able to produce a single title deed record, a single company share, a single tax return or a single judicial file. In terms of law, this situation is very clear: The burden of proof is on the claimant and an unproven claim is not political criticism, but a criminal allegation targeting personal rights. Gürsel Tekin's asset declarations during his time as an MP and party executive have been subject to legal scrutiny, and there have been no lawsuits filed or finalized to date. Therefore, what is at stake here is not “suspicion” but a deliberate perception operation. Instead of discussing the political line, inventing fictitious property lists is a sign of not being able to produce politics, but being unable to produce politics. Such allegations document not Gürsel Tekin, but the political and moral bankruptcy of those who think they are doing politics by disregarding the law.

Cynicism The Political Accumulation that the CHP is Beginning to Be Ashamed of

Politics with regiments is politics that knows the field and lives with the organization. In the CHP's transformation in recent years, there is an increasing distance from this political accumulation. However, cynicism is the memory of politics and this memory is strengthened by preserving it, not by liquidating it.

“The Political Function of the Accusation of ”Greed"

“The accusation of ”ambition" is a political label used to render invisible those who avoid responsibility, not those who take responsibility. Gürsel Tekin's practice represents the will to take responsibility rather than ambition.

Expulsion Debate: A Question of Model, Not Discipline

This debate is not a technical disciplinary process, but a choice of a model for what kind of party the CHP wants to be. Purging those who are uncomfortable creates a sense of order in the short term; in the long term, it depoliticizes the party.

Survey Data: Social Response, Not Noise

ORC Research data show that the negative discourse against Gürsel Tekin does not have a broad social response.

“İtirafçılarla ve sorunlu aktörlerle kurulan siyaset ilişkilerine yönelik eleştiriler haklıdır” diyenlerin oranı %62,7’dir.

“Göreve geldiği günden bu yana başarılı bir yönetim sergiliyor” değerlendirmesi %64,1’dir.

Genel seçmende olumlu değerlendirme %63,1, CHP seçmeninde %59,2’dir.

Conclusion: Organized Politics on Trial, Not One Person

The Gürsel Tekin debate is not a matter of an individual political career. This debate is a historical threshold on whether organized politics will survive in the party. The question is not whether a name takes the right or wrong step; it is a question of through which channels, with which actors and by taking which risks. In times of crisis, is it acceptable to take responsibility or to retreat? Will those who disturb be protected or those who remain silent be rewarded? It is precisely these choices that are on trial.

The issue facing the CHP today is not merely a question of internal organization or discipline. It is a question of direction that will determine the nature of the party's relationship with the organization. Will the organization be the subject of political struggle or an apparatus that implements the decisions of the center and can be suspended in times of crisis? Without answering this question, no structural problem can be solved.

Organized politics is inherently risky. It is uncontrollable, it is uneven, it does not always conform to centralized plans. However, this is precisely where political dynamism emerges. Actors who are in contact with the field, who know the neighborhood, who directly feel social tensions are also the early warning system of politics. Purging these actors by declaring them “too talkative”, “too disturbing” or “incompatible” may create a sense of order in the short term. But in the medium and long term, this choice depoliticizes the party, reducing it to a technocratic administrative apparatus.

This is precisely one of the main crises facing the opposition today: Politics is increasingly confined to a risk-free, conflict-free and sterile space. However, in a country like Turkey, where deep inequalities, structural poverty and harsh power relations prevail, risk-free politics is not possible. Politics that does not take risks, politics that does not generate tension, can only manage the continuation of the existing order; it cannot transform it.

Therefore, the solution lies not in expanding disciplinary mechanisms, but in increasing the channels of political participation. What the CHP needs is not to silence those who object, but to turn objection into an institutional power. Intra-party pluralism is not a weakness; it is the greatest political capital when managed correctly. The voice of the organization should be seen as a compass that determines the direction of politics, not a noise to be drowned out in times of crisis.

Another critical issue is the relationship between politics and law. Legal mechanisms can be a tool to overcome political deadlocks, but they cannot replace political will. Referring problems that should be solved by politics to the judiciary may seem comforting in the short term, but in the long run it neutralizes politics. This is why the call committee debate is not just a matter of procedure; it is a test of whether politics can defend its own space.

There are two paths ahead for the CHP. The first path is the one that deepens centralization, pacifies the organization and reduces politics to a narrow administrative activity. This path is conflict-free, but also ineffective. The second path is one that puts organized politics back at the center, strengthens its connection to the field, and multiplies rather than suppresses uncomfortable questions. This path is risky, but it is the only way in which politics can be truly re-established.

The Gürsel Tekin debate is a moment when the choice between these two paths becomes visible. The decision made here will determine not only the present, but also the kind of opposition line the party will build in the future. Strong parties grow not by diminishing their offspring, but by multiplying them. They grow stronger not by excluding those who object, but by keeping them within the system.

It is therefore not a person on trial here.

Organized politics is on trial here.

It is the field-based opposition that is on trial here.

It is the truth that is on trial here, that disturbs comfort.

And politics can only truly grow when it confronts this truth, when it risks conflict and makes the organized will a subject again.